THE MANIFESTO OF STENCILISM

by Blek le Rat

I saw wildstyle graffiti for the first time during a trip to New York in 1971. There was an incredible profusion, in the subway, on the walls surrounding basketball courts, graffiti drawn in marker, nestling signatures surmounted by a crown, spray-painted lettering, filled with swirls and colors, everywhere I looked. I was so intrigued by these illuminations I remember asking the inevitable question:

What does this mean and why do so many people do that ?

Blek le Rat

Unfortunately no one could give me a satisfactory answer, except that it was the work of thoughtless and irresponsible people. I found that people engaging in graffiti were generally known as a “dirty bunch,” and called such by John Vliet Lindsay, mayor of NYC from 1966 to 1973. At the same time in Paris this means of expression was still in a latent state. Of course there was the political and social demands scribbled on the walls of the city in 1968, and of course we had addressed the subject through posters of protest created in the social workshops at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, but there was yet to be a movement of artists investigating the urban landscape and acting out artistically within it.

Yet the street art movement had already existed in the United States since the mid-60s when dozens of artists, condemned to urban anonymity, sounded the alarm, writing their tags on walls, in spray paint or marker.

The graffiti I saw in New York remained firmly planted in my memory though acting out my own graffiti took ten years to hatch. Studying fine arts and architecture during the 70s at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris familiarized me with the techniques that would come in handy later, in my work on the street. I became well versed in the techniques of etching, lithography and screen printing, and all of these methods, along with the study of architecture at the Architectural Teaching Unit # 6, made me aware of the intricacies of planned urban space. It was also in the early 70s that I was largely influenced by David Hockney, who had a major exhibition near the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. . I can say that his work is the most impressive thing I had ever seen in my life. The following year Hockney made a film titled,“The Bigger Splash”,in which he uses oil to paint the image of one of his friends on the wall of an apartment; the image has never left my mind. I thought this film was so important to the history of art that I watched it over and over, as many as ten or fifteen times.

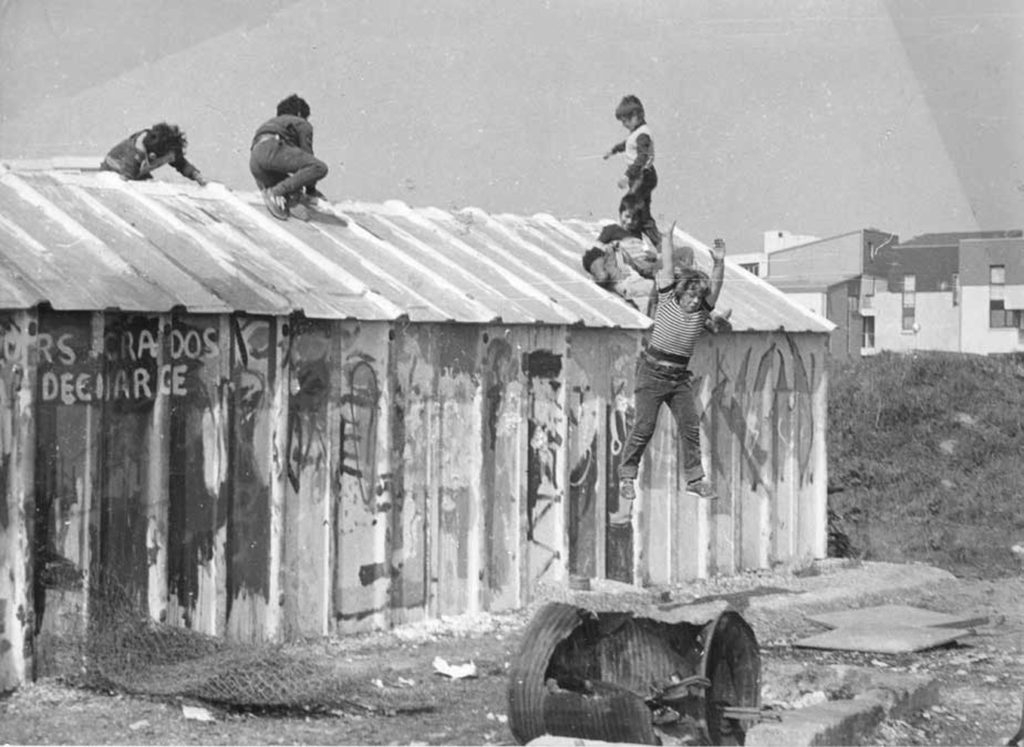

In 1980 my friend Gerard and I worked at an adventure playground in the town of Les Ulis, designed for pre-teens during the school holidays. I was working as a volunteer on this adventure playground. It was a place inhabited by young children who came to meet other children without the world of adult authority intruding upon their games. The playground was located directly behind a supermarket and people the children frequently came and went between the two. Among the discarded trinkets from the store, one could regularly found find paint cans which were removed illegally from the store and used to paint and repaint the cabin in which we kept our equipment.

Big, dripping Frescos following no particular style appeared throughout the year and were routinely painted over. Gerard and I were moved by each and every creation and we decided to get some spray paint of our own out of the desire for modernity. We had caught the bug. The capital was ours, we needed only to act. The first time we did graffiti, in October 1981, Gerard and I tried to reproduce the American styled graffiti on an abandoned wall in the fourteenth arrondissement of Paris, on Thermopylae Street. It was a fiasco! None of the imagery turned out well. I then suggested we make stencils — a very old technique that was an ancestor to screen-printing and later used by far-right Italian political factions in their propaganda.

After remembering the stencilled image of the Duce helmet I’d seen in the early 60s, a remnant of WWII, during a trip I took with my parents to Padua, Italy.

We finally had the technique and the equipment, we had only to act.

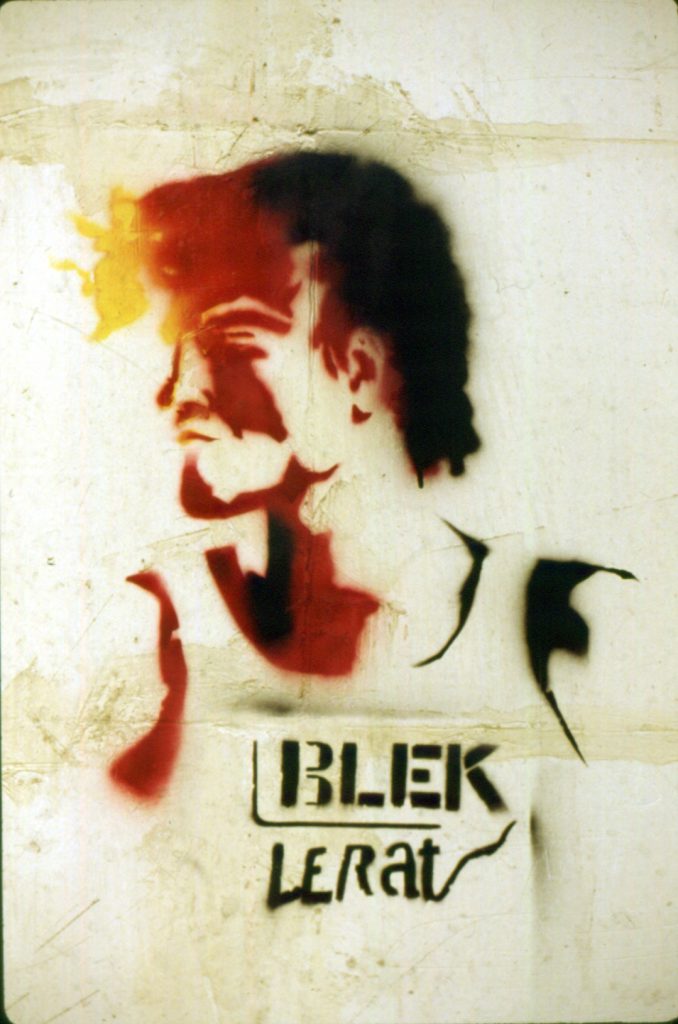

The streets of Paris afforded us ample space to work in, and the practice of graffiti was completely unknown at that point, so the roaming police rarely disturbed us unless they wanted to know what we were doing and whether our agenda was political. We answered: “No it’s art”, and the game was won. Gerard and I used the name BLEK in reference to an Italian comic book that we read in our childhood called Blek le Rock. We chose to use a pseudonym because we decided we wanted to remain anonymous as a way to challenge the locals.

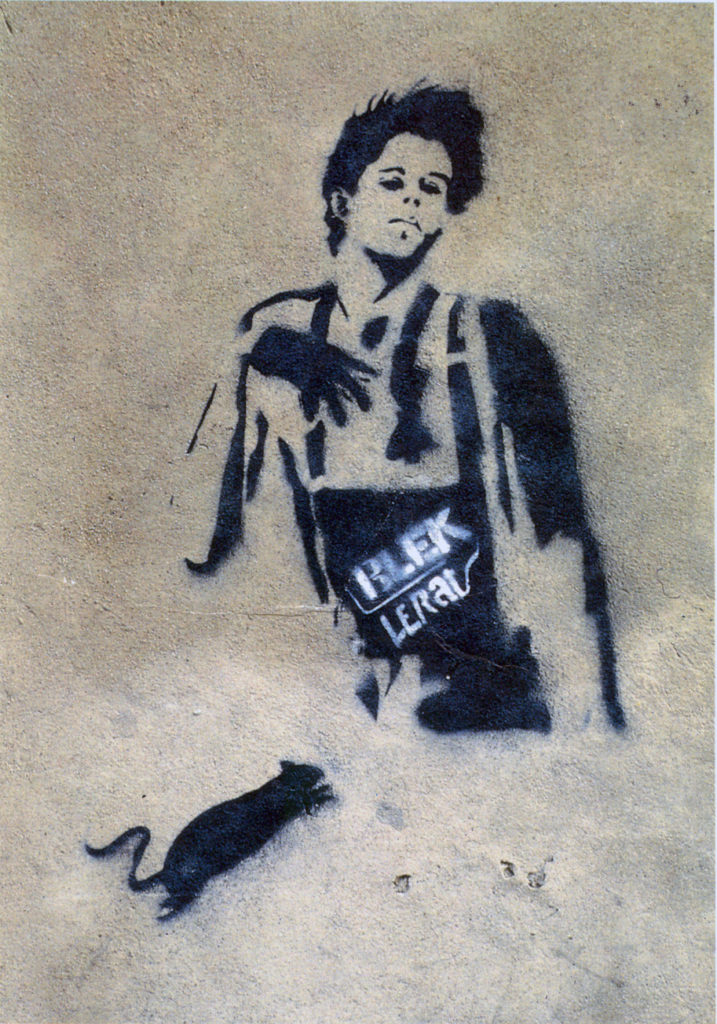

Who were the authors of these little rats, these bananas, the little running men and all the little stencils that we made during the day and sprayed come night throughout the fourteenth and the eighteenth districts of Paris?

Over time, our nocturnal outings became more and more frequent. On December 31st in 1981, we decided to stencil the temple consecrated to Modern Art: the Centre Georges Pompidou.

Blek le Rat

That night in the freezing winter cold, we painted lots of rats, tanks and small figures on the Centre Pompidou, a place where people come from all over the world to worship art. Museum guards came out to ask what we were doing there. As when we had been questioned by the police, we answered “art,” to which the guards responded with a slight smile. In 1983 the duo that made up BLEK separated when Gérard developed other interests he wanted to pursue. Upon finding myself without a partner, I decided to adopt Blek le Rat as my nom de plume.

THE NAME IS THE RELIGION OF GRAFFITI.

Norman Mailer

It is through the name that we are recognized, tracked, the image becomes a support to the name, the name that told me: « You exist for thousands of people you do not know and you will never meet, but you exist in this closed world of urban anonymity. ».

I felt empowered to paint and avoid the middlemen who would judge my work with their values. I had found liberty within the anonymity of my work, a form of freedom. I was alone in the city and the city was mine. After a night spent painting, I would pass by my walls again and again, sometimes standing for hours looking at my work and the people passing by. The smallest glance they gave my graffiti filled me with joy. My enthusiasm had me creating more and more of the ephemeral images, with the wear and tear of painting on the streets, individual stencils don’t last very long. Dried paint eventually forms a crust around the stencil’s edge and the cutout sections close up after being sprayed several times. New stencils always have to be made; the more I worked, the better my technique became, and with improved technique, the easier it was to do better work faster.

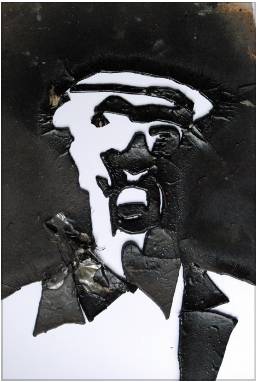

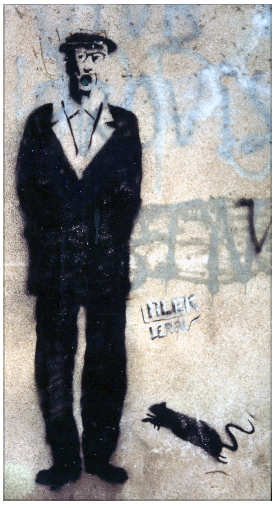

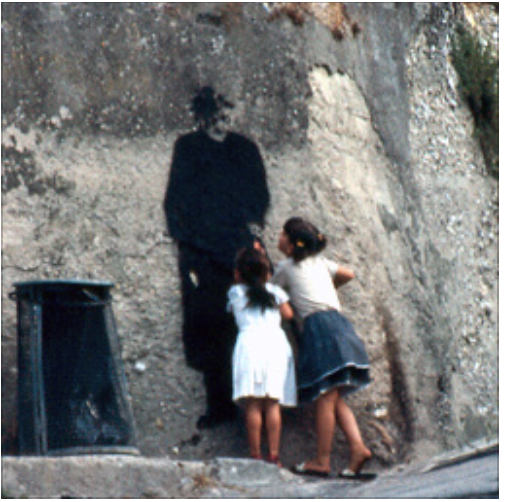

In March of 1983 after mastering my technique, I came up with the idea of making a life-size stencil. I found a photo of an old man wearing a cap in the newspaper Libération. Taken in Northern Ireland, the photo suited my needs perfectly. This character would stroll through the streets of dozens of cities in France, left as a hint of my passage. He became known as “Buster Keaton,” “Charlie Chaplin” and “the old man,” and eventually took on a dimension that I had not originally intended. His figure became famous in an unexpected way: The public was enamored with the image, and the photojournalists were in a frenzy to capture each painting that I put up.

During that time, I would often stumble onto printed photographs of my figure in various newspapers beside articles that were unrelated to graffiti. Because this venture was so successful, many other life-size stencils followed, all of which resembled me in some way and with whom I felt an affinity.

There was Tom Waits, a little boy in short pants, Andy Warhol, Marcel Dassault, The old Man with a Stick, a woman and child, a Russian soldier that I painted at every exit of the main périphérique around Paris, President Mitterrand, a faun, Joseph Beuys, a man simultaneously running and screaming, two dogs in mating, and a woman in garter belt—stenciled on the entrance to Serge Gainsbourg’s house and other appropriate places.

They were my characters, and I think they all resembled me somehow. They introduced me to the world like a person would introduce himself to another (person) and when As I paint my characters, I always feel as though I am leaving a part of myself on the walls of the cities around the world that I’ve visited.

During the summer of 1984 stencils other than my own began to appear on the walls of Paris. The first I saw were signed by Marie Rouffet and Surface Active. A dialogue had been established between us and their graffiti were complementary to mine; it was as though we shared a private joke between us, which did not displease me, and aroused in me a myriad of thoughts about this new language, of hieroglyhpics that we had in common.

. While stencil graffiti flourished in Paris the surreptitious repression(that was the criminal justice system) began to stretch out its feelers. The cops were becoming more aggressive and I experienced my first arrest in Les Halles. It was my first time in police custody, my first police report, my first questioning by a detective. Fortunately for me, this detective was a fan of comic books and did not transmit the report to the prosecutor. Nothing came of the arrest,

but the fear of being caught became very real soon after and has never left me from the end 84. From that moment on, I studied the habits of the cops, their comings and goings, which days they had off and the times they made their rounds. I learned to hide my equipment under cars, to have friends watch the streets where I was going to work, and finally, I got used to taking more precautions as my activities became illegal and the penalties increasingly severe. Despite this unbearable game of hide-and-seek, the desire to express myself, to paint, was so strong that the tension was transformed into an endless flood of creativity when the time came to work. For there is no greater joy for me than to work on the streets in the depths of a winter night, when my hands freeze and the heart burns in fear.

Throughout the years, I continued to be anxious about the possibility of incarceration. It was in October 1991 when that fear became a reality. I was ordered to appear before the Parisian court for the crime of damaging property belonging to others. I was again fortunate enough to come across a judge who loved my work and said: “I can not condemn you for this, it’s too beautiful,” after looking at a photo of my stencil my lawyer had given him.

Urban artists have simply the intention to speak via images ; these images are intended words to the community: paroles of love, of hate, paroles of life, and of death. It is a kind of therapy; a therapy which showcases elegance, refinement, and attempts to fill the gaps of this horrible modern world, to cover urban areas with images of joy and catch the eyes of passers-by in the early morning as they begin their day.

But the authorities are implacable in their reaction to street art, declaring war on graffiti, and using the the law to hold over the heads of these young artists a punishment that is not equal to their misdeeds. They threaten street artists with huge fines, as if our cities have more to fear from unsanctioned artwork than drugs. The immense desire to paint and to express ourselves through our imagery, has been so strong that urban artists around the world have made this movement the most important of the century, with its profusion of images and the number of its people who participate. One has only to look at the scope and breadth of our work across the globe to see how far we’ve reached and the authenticity of our messages. There is no place left in the world where we have not left our traces. Even in Peking, under the strictest governmental regime, there is a man leaving his mark right at this moment.

Though public opinion is slowly turning in our favor, most of society still considers urban art as a kind of prolific leprosy—a spreading blemish on the public façade . It is my belief that the metropolis blooms with poetic intentions inspired by the colors of our aerosol cans.